Written By Neil Maedel

During the 1990’s the Author’s Zurich Switzerland-based ProTrader Newsletter identified some of the sector’s most successful exploration and development stocks while chronicling the resource bull market .

The Coming Gold Stock Bull Market

If ever there was a time to invest in the gold sector it is now.

The 1990’s began in the shadow of the 1987 stock market crash, with a deflationary tailwind powered by more than a billion new entrants to the West’s labor supply – mostly from China and Eastern Europe. Forced commodity sales, from Russia and the addition of massive new copper supplies from South America, further dampened prices. In reaction to the 1990 Persian Gulf War, oil began the decade at a high of US$41 per barrel. It was a windfall for a struggling Russia, which did not last. Saudi Arabia, perhaps beholden to its American Gulf War rescuers, made sure oil supplies were plentiful in the ensuing decade, driving its price to a 1999 low of US$9.54. Copper fared little better falling from $1.36 to $0.61 during the same period. Gold’s price, which was impacted by the forced sale of reserves by Russia, dis-hoarding by many of the World’s Central Banks and hedging by some of the world’s largest miners, fell from US$422 in 1990 to a low of US$255 in 1999.

Contrary to what one might expect, Canada’s Junior Exploration sector thrived for most of that decade as relatively low exploration costs together with advances in geological understanding and the opening of new areas, combined with a thriving resource ecosystem to produce a series of giant mineral discoveries. Small brokers provided financing for the resource juniors and the plumbing for a healthy middle class with money to invest. The result, as Economist John Maynard Keynes’ might describe it, was animal spirits which continued to grow with each new discovery and with it billions in risk capital looking to grubstake the next exploration idea.

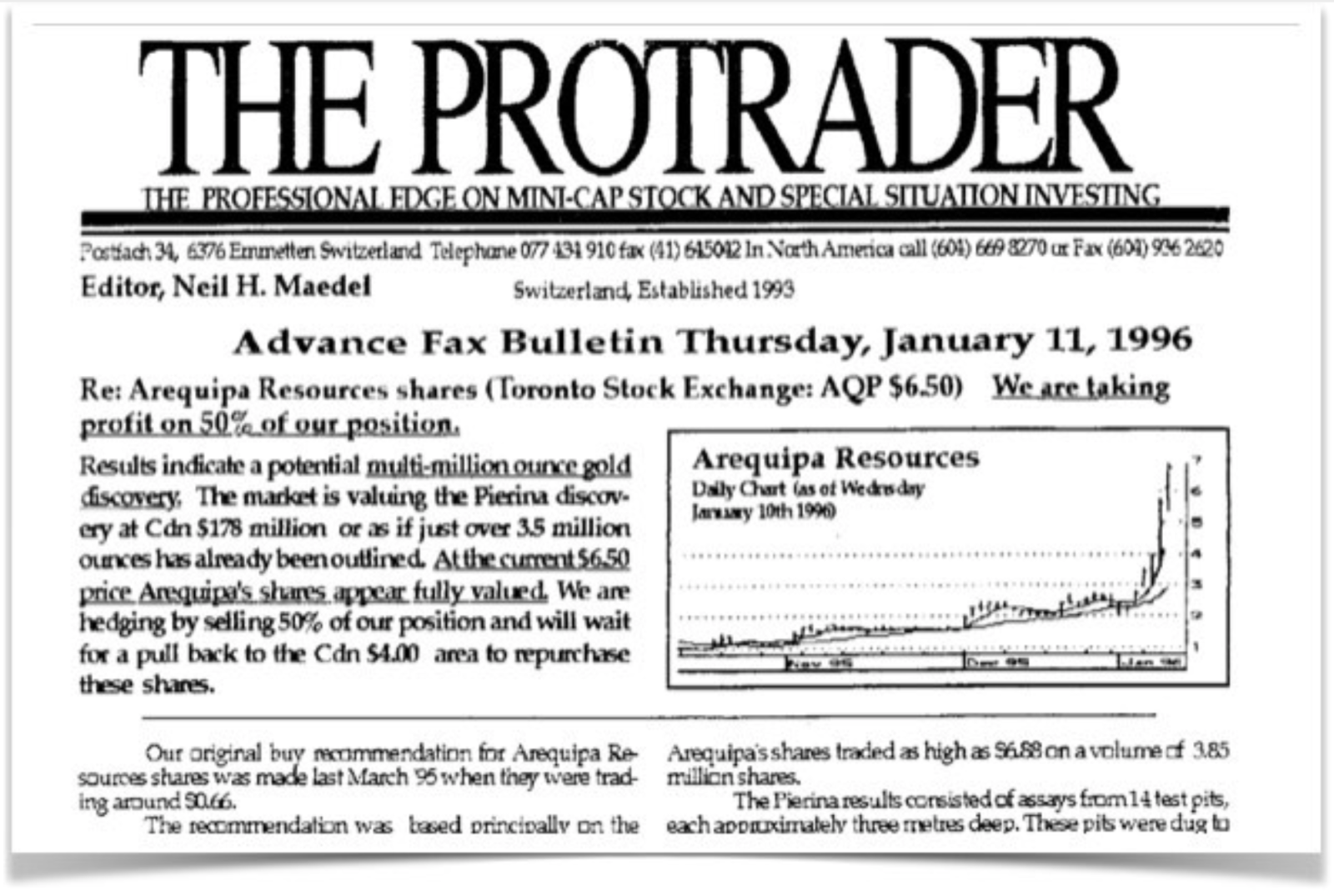

It was in 1988 that the discovery of one of the richest gold deposits in history at Eskay Creek, British Columbia set the sector alight. The discovery propelled the shares of Calpine Resources and Consolidated Stikine a respective 16,250 and 27,127 percent higher. The subsequent revelation of a diamond find by Diamet Minerals at Lac de Gras, NWT set its shares rocketing from CAD$0.22 to $60. Southern Era shares then rose 24,000 percent. This was followed by a major gold find in Peru by Arequipa Resources’ and a massive nickel discovery in Voisey Bay, Newfoundland by Diamondfields Resources. Many more micro-caps went on to make mineral discoveries of varying sizes and as a consequence further enriched an increasingly enthusiastic public. The concept that small companies could regularly discover giant deposits was starting to seem, well, normal.

Sir John Templeton famously remarked that “Bull markets are born on pessimism, grown on skepticism, mature on optimism and die on euphoria” and both the beginning and the end of the 1990’s resource bull market was no different. Despite its outsized claims, Bre-X Resources met with little skepticism and a euphoric reaction when it announced a giant gold discovery in Busang, Indonesia. Investors bid its shares from CAD$0.50 to the equivalent of CAD$286. But when holes drilled by Freeport McMoran to verify the discovery proved to be barren, the bubble was pricked as Bre-X shares collapsed, taking the rest of the resource market with it.

In hindsight, the resource bull market and bubble was at first driven by compelling fundamentals. Economic mineral discoveries were being made often enough and in a quantity that a lot more wealth was produced (and put in the pockets of investors willing to speculate) than the amount that was spent exploring.

Richard Schodde, the founder of Australia based MinEx Consulting, is an expert regarding long term trends in the industry and is known for his intensive level of analysis. For example, MinEx’s research on the gold sector includes data on over 55,000 gold deposits globally. The key observation from his work is that between 1988 and 1997 the estimated value of gold discoveries globally ranged between two and five times the amount spent on exploration every year. In short, gold exploration was a good business and investors, at least in the early years, reacted rationally by flocking to it. In contrast, for the period from 2009 to 2018, according to Schodde the value created only covered 46% of the amount spent on exploration. In other words, of every dollar spent, US$0.56 was lost. Exploration costs had become too expensive compared to the wealth they produced. As you would expect, investors have also acted rationally by deserting the sector.

As Schodde points out, this is a notoriously cyclical business and his research shows that after peaking and greatly exceeding the value of gold discovered, exploration costs have dropped dramatically since 2012 just as the value of gold deposits are increasing. His work estimates that on average they have fallen from a 2012 peak of US$97 per oz/Au discovered to US$37 oz/Au in 2018. This brings costs back towards the high end of the range experienced in the 1990’s. Gold is, however, more than quadruple the average 1990’s price a reality which should more than make up for the cost difference. With gold testing the US$1700 level and likely to move higher, the value produced is likely to once again materially exceed the costs of exploration. At the same time a growing number of previously marginal gold deposits are becoming worth developing as gold’s price increases. These companies are likely to provide the first relatively low risk opportunities to make money at the initial stage of the cycle.

This is the key difference between the early 1990’s and now. Gold’s price had peaked at US876 per ounce in December 1979 – more than twice the price it traded at when the 1990’s bull market started. Any known deposits that became economic when gold traded in the US$300 to $400 range where the 90’s bull market began were likely to have already been developed in the decade previous. So there was no wave of new cash-flowing or deposit-developing juniors to be acquired by larger companies because gold was trading at US$400. Instead the 1990’s bull market was driven principally by mineral discoveries which led to takeovers such as BHP Billiton’s acquisition of Diamet or Barrick Gold’s purchase of Arequipa Resources and so on.

In this current cycle, the rise in gold’s price is most likely to initially stimulate the development of formerly sub-economic gold deposits. As these deposit’s viability is established and larger gold producers become more confident that the high gold price will continue, some of these companies will be acquired. These acquisitions normally become market-driving benchmarks for the sector, just as their respective buyouts add to the pool of speculative capital.

Finding companies whose deposits have become economic as a result of a rising gold price is relatively straight forward. Guessing when and where the next giant gold discovery will occur is anybody’s guess. And it is a much riskier proposition. Far more so than developing and putting an already known deposit into production to generate revenues. Many small-cap gold deposit developers will not get beyond establishing their deposits’ new economics as they are acquired by larger gold producers looking to grow.

Sir John Templeton’s “Bull markets are born on pessimism” is as true now as ever. It has been only two years since gold traded at a low of US$1156, gold is currently testing US$1700 and yet the TSX Venture Resource index is no higher now than it was then. The lack of a reaction is not surprising. Gold juniors usually don’t react immediately to a rise in gold’s price (at least not until near the terminal stages of the rise). There is usually a substantial lag especially at the beginning of a bull market. We saw this in 2015-16 in the early stages of the rally. It takes time for public recognition or, later on, for industry leaders to react in substantial ways, such as by arranging major financings or takeovers which establish a higher price regime.

This is where I see an immediate opportunity. Currently the TSX.V Resource Index is at 22.38 – roughly where it was a month after gold had reached a rock bottom US$1046 in 2015. The index did not react to the beginning of gold’s increasing price until January 20th – six weeks later. When the index did finally break out, it exploded upwards – tripling in a matter of months. Investors that were not already positioned likely paid a lot more for their shares. Critically, however, at that time exploration costs still exceeded the value created. Gold’s rally then stalled at US$1373 (nearly US$300 lower than it is now) before falling all the way back to US$1160. With gold now more than US$500 per ounce higher and the index still near its 2015 and 2018 lows, logically, it is time to start looking hard at the sector. The value proposition is quite clear.

This is where I see an immediate opportunity. Currently the TSX.V Resource Index is at 22.38 – roughly where it was a month after gold had reached a rock bottom US$1046 in 2015. The index did not react to the beginning of gold’s increasing price until January 20th – six weeks later. When the index did finally break out, it exploded upwards – tripling in a matter of months. Investors that were not already positioned likely paid a lot more for their shares. Critically, however, at that time exploration costs still exceeded the value created. Gold’s rally then stalled at US$1373 (nearly US$300 lower than it is now) before falling all the way back to US$1160. With gold now more than US$500 per ounce higher and the index still near its 2015 and 2018 lows, logically, it is time to start looking hard at the sector. The value proposition is quite clear.

But where to look? Guessing which company will make the giant discovery is not for the faint hearted. What we can do with more certainty is use known data to calculate which gold deposits are likely to have become viable given the higher gold price. If the company has the expertise required to execute, we are more than half way to a profitable exit. It is these few that can offer the nearer term, lower risk potential for exceptional growth and profit in a gold-cycles’ early stages. Later on, their shares are likely to be much more expensive to buy, if they have not already been acquired by mid-cap gold producers.

Sonoro Metals, where I am an Executive Director, is pursuing this model with its planned heap leach mining gold operation. It is in the final stages of recruiting a China-based mine engineering procurement and construction company for the provision of project debt finance (which avoids share dilution) and the development of its Cerro Caliche deposit in Mexico. Sonoro’s management has collectively either discovered or developed and operated more than a dozen gold deposits. So there is no question they have the expertise required. The initial gold operation is intended to finance exploration and growth giving it a potential which is not small.

Sonoro has a great business case, just as the overall gold sector does with its reduced exploration and development costs, new potential for the development of existing deposits and the substantially increased gold price. To paraphrase economic historians Reinhart and Rogoff, ‘This time is not different.’ Similar to the 1970’s, the early 1990’s and the millennium, the prerequisite business case is now in place. And it should soon underpin a major resource gold stock bull market. The pessimism which exists today is no different from the gloom which followed the 1973-74 and 1987 stock market crashes, 9/11 and the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis. All provided exceptional opportunities to position for a subsequent upward precious metals’ cycle. With, as Schodde demonstrates, costs down, gold’s price dramatically higher and central bank liquidity pouring in, if ever there was a time to invest in the gold sector, it is now.

Forward-Looking Statement Cautions: This post may contain certain “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of Canadian securities legislation, relating to, among other things, the Company’s plans for the drilling of the above-described Cerro Caliche Concessions, located in the municipality of Cucurpe, Sonora, Mexico, and the Company’s future exploration plans for those properties. Although the Company believes that such statements are reasonable based on current circumstances, it can give no assurance that such expectations will prove to be correct. Forward-looking statements are statements that are not historical facts; they are generally, but not always, identified by the words “expects,” “plans,” “anticipates,” “believes,” “intends,” “estimates,” “projects,” “aims,” “potential,” “goal,” “objective,” “prospective,” and similar expressions, or that events or conditions “will,” “would,” “may,” “can,” “could” or “should” occur, or are those statements, which, by their nature, refer to future events. The Company cautions that forward-looking statements are based on the beliefs, estimates and opinions of the Company’s management on the date the statements are made and they involve a number of risks and uncertainties, including the possibility of unfavourable interim exploration results, the lack of sufficient future financing to carry out exploration plans, and unanticipated changes in the legal, regulatory and permitting requirements for the Company’s exploration programs. There can be no assurance that such statements will prove to be accurate, as actual results and future events could differ materially from those anticipated in such statements. Accordingly, readers should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements. The Company disclaims any intention or obligation to update or revise any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except as required by law or the policies of the TSX Venture Exchange. Readers are encouraged to review the Company’s complete public disclosure record on SEDAR at www.sedar.com.

THIS PRESS RELEASE DOES NOT CONSTITUTE AN OFFER TO SELL, OR THE SOLICITATION OF AN OFFER TO BUY, NOR SHALL THERE BE ANY SALE OF SECURITIES OF THE COMPANY IN ANY JURISDICTION IN WHICH SUCH OFFER, SOLICITATION OR SALE WOULD BE UNLAWFUL PRIOR TO REGISTRATION OR QUALIFICATION UNDER THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY SUCH JURISDICTION.

Neither the TSX Venture Exchange nor its Regulation Services Provider (as that term is defined in the policies of the TSX Venture Exchange) accept responsibility for the adequacy or accuracy of this release.